Farmed. Hatchery. Wild.

I fed a rusty orange streamer into the current, threw an upstream mend, and let it swing. We call it First Water. It’s what you get early in the morning when you get to the river before the next guy. First Water makes you smile after a hard week at work. Like making lemonade out of lemons.

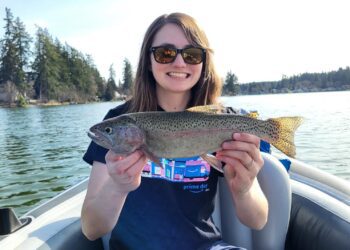

A trout hammered the fly and the tippet snapped. Heart pounding, I cut the leader back to 8-pound, tied on another fly and cast quartering-down. This time when the fish hit, it turned and charged, coming straight out of the water. Five minutes later we slid the net under a four-pound gnarly, hook-jawed brood stock rainbow. We have learned from experience it’s hard to revive the big hatchery rainbows, so it was an easy decision to keep it for the table.

FARMED, HATCHERY, WILD OR NATIVE?

Here’s a thing that doesn’t make sense. We go to the grocery store and complain about the price of groceries and then we drive to the lake and catch and release a limit of rainbow trout at $10 a pound. I’ve done it.

Hey, those fish were put there to catch and keep. It’s healthy food, high in omega-3 fatty acids and B vitamins. Easy to catch (sometimes). Easy to clean. Tastes good. Good for you.

Think of it like this: we have rainbows, cutthroats, brook trout, brown trout, bull trout, and lake trout in our lakes, rivers, and hatchery raceways. Some of them end up behind the butcher’s glass at the grocery store. How do we tell where they came from? The ones in the cellophane and Styrofoam, that’s easy. Those are farmed fish, which are generally shoveled a high-quality pelletized food and then fed a carotenoid called Astaxanthin which gives the meat an orange color and improves the taste.

According to Luke Allen, from the Wizard Falls Hatchery and Tim Foulk from the Fall River Hatchery, astaxanthin is produced by microalgae which is ingested by small fish and invertebrates like krill, which are then ingested by fish.

In Oregon, hatchery-raised rainbow trout (and cutthroats) are classified as legals (usually 8 to 12 inches), trophies (usually 14 to 18 inches), and brood stock, which are the surplus breeding trout that tip the scales somewhere between four to ten pounds. In Central Oregon, these fish end up in places like Pine Hollow Reservoir, Walton Lake, South Twin, and Fall River. Hatchery trout may also be released as fingerlings in waters like Lava Lake, East Lake and Diamond Lake where the natural feed is so good the fish grow fast. Fingerlings are also released in the high lakes every other year. Fingerlings, although raised in hatcheries in geometric order, tend to behave and look more like wild trout as they reach a harvestable age.

The terms wild and native can refer to the same fish or mean two different things. Brown trout, brook trout, and lake trout are not indigenous to Oregon but were introduced. Browns come from Germany and brooks come from the East Coast. That’s why we refer to them as German browns and Eastern brooks. But if they were hatched in gravel we call them wild trout.

Photo courtesy Don Lewis

The term native is inclusive of rainbows, cutthroat and bull trout. In some cases these fish may be caught, kept and eaten, but it’s a good idea to release them to spawn and prosper. If you catch a brookie in the high lakes, hey, that’s some of the best wild food you can get. And you are not eating a native fish.

A steelhead is a rainbow trout that migrated from freshwater to the ocean and returned. If a person eats farmed steelhead, it is probably not steelhead at all, but rainbow trout packaged as steelhead. An angler that catches and eats a fin-marked steelhead has consumed a hatchery steelhead. Surplus steelhead that returned to their hatcheries in places like Nehalem or Three Rivers are often trucked to coastal lakes and set free to give anglers another chance at them. Because they will probably not thrive in the lake, the highest use of these fish is to turn them into a good meal.

Fisheries managers sometimes struggle with the divide between the consumptive and the catch-and-release ethic.

Diamond Lake was devoid of fish before it was stocked by mule trains in the early 1900s. The food-rich lake still grows fish to trophy proportions and not enough gets taken home by sportsmen. It’s a resource we could be making better use of, and the same principle applies all over the state from Lake Selmac to Wallowa Lake to Bikini Pond to Rock Creek Reservoir to Lava Lake. Those fish are there to eat. And there are some really good things like dill, parsley and lemon that go great with a pan full of eastern brookies or hatchery ‘bows.

That’s why I say when life gives you lemons, go catch a trout.

For a copy of the Fishing Central Oregon book, send $29.99 to Gary Lewis Outdoors, PO Box 1364, Bend, OR 97709 To contact Gary Lewis, visit www.GaryLewisOutdoors.com